If you think our tax system is fair, you’re probably older than me

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

If I were to propose to you that people earning the same amount of income should pay about the same amount of tax, you would probably agree. It’s only fair, right?

Economists call this principle “horizontal fiscal equity”. But that term has fallen by the wayside, perhaps because the Australian taxation system has strayed pretty far from it.

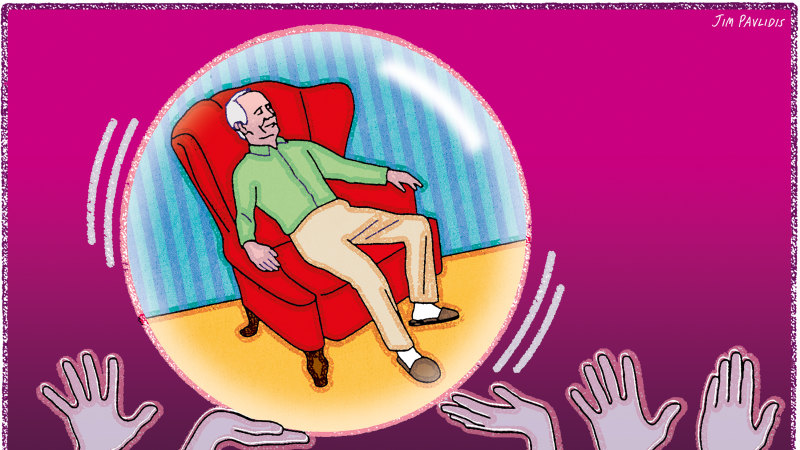

Illustration by Jim PavlidisCredit:

How you earn $100,000 in Australia determines how much of it you get to keep. If your income is from superannuation, it’s tax-free to withdraw after the age of 60 (after being taxed at a concessional rate of 15 per cent). If it’s from capital gains, you can get a 50 per cent tax discount (or a 100 per cent discount if your parents got on with it early enough for you to have bought your assets back in 1985). And if you’re over 67, and a pensioner, you get a senior tax offset.

Most of these don’t apply to someone starting off in their career. Unlike many older generations, most young people haven’t built up wealth by owning assets like housing, or an income stream through owning large amounts of shares. And withdrawing from super isn’t really an option. Young people’s main source of income is wages.

So, not only do they miss out on many tax concessions, they also cop the brunt of what we call “bracket creep”. This is where, as inflation – or the general level of prices – rises, your income gets pushed into higher tax brackets.

Of course, as part of a progressive tax system, it’s fair for higher incomes to be taxed at higher rates. The problem is when the price of everything is also surging, as we’ve seen in the past couple of years, because it means the purchasing power of your income falls. Basically, if you’re earning more, but the things you’re paying for, like rent, food and petrol, get more expensive, you’re not necessarily much better off. Your purchasing power and real wage (what you earn, adjusted to account for inflation) will be a lot lower. And yet, a larger proportion of your income will be getting taxed at higher rates because on paper, you’re earning more.

HECS debt increases in line with inflation so many young graduates have seen a jump in the amount they owe.Credit: Peter Braig

This affects everyone earning a wage, but remember, for young people, it’s often their only major source of income. And while the government has pledged to keep the stage three tax cuts intended to ease bracket creep, it mainly benefits middle to high-income earners, of which young people don’t tend to form a large part.

But, that’s not all. If you think young people are getting it rough recently, tax isn’t the only thing being deducted from their pay.

Many will have taken out an interest-free loan to fund their higher education, called HECS/HELP.

The interest-free part is good (though not quite as good as the free education some readers will remember). But it’s another bite taken out of young people’s income at a time when cost of living has jumped. And while HECS/HELP doesn’t affect our credit scores, it does reduce borrowing power.

The good news is that the repayment threshold, the point at which you have to start paying back the debt, and the progressively higher rates you have to pay it back at have been raised roughly in line with inflation. In the 2022-2023 period, you would have started repaying your HECS/HELP loan once you hit an income of $48,361. For the 2023-2024 period, that starting point has been lifted to $51,550.

But as young people would be acutely aware, the HECS/HELP debt itself also increased in line with inflation. And if you’re freshly graduated with a lot of your loan left to pay back, that means a big leap in your HECS/HELP debt (7.1 per cent this year to be exact). If you’re like me, that means you might now have an even higher debt to pay back than you did when you left university.

And if you think bracket creep is bad, you might be surprised by the seemingly arbitrary jumps in compulsory HECS/HELP repayments between income brackets.

Some people may have noticed they’re losing a larger proportion of their overall income to HECS/HELP debt. That’s because instead of a marginal repayment rate – where you only pay the increasingly higher rates on income earned above each threshold – HECS/HELP debt is paid back through an average repayment rate, meaning every time you enter a higher rate threshold, your entire salary gets a bigger cut taken out of it.

At a salary of $59,518, one per cent of your income is taken by the tax office to pay back your student loan. Earn $1 more, and it’s not just that additional $1 that gets the higher rate of 2 per cent bitten out of it, it’s 2 per cent of your entire $59,519 salary. You’d pay about $595 back on your loan on the first salary, then suddenly $1190 on the salary that is $1 higher.

The past couple of years have been tougher for everyone but young people have been copping the brunt of it. The tax and repayment systems we have in place weren’t built with high inflation in mind, and certainly wasn’t built by, or for, those now entering the workforce. You might be wondering why young people aren’t making a bigger deal out of it. If you ask me, they’re busy enough just trying to get by.

Millie Muroi is a Herald business reporter.

Get a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up for our Opinion newsletter.

correction

A previous version of this article stated that HECS/HELP debt had gone up 7 per cent this year. It has gone up 7.1 per cent.

Most Viewed in Money

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article